The latest title in the Blue Danube imprint, which focuses on literature, history and travel in Central Europe, is Venetian Angel, a short novel by Ferenc Molnár, now translated into English for the first time. Molnár was a famous pre-war dramatist whose many plays included one on which the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Carousel was based. Here, in the introduction, his grandson Mátyás Sárközi writes about the author:

Ferenc Molnár, my grandfather, had to leave Hungary in 1937 because of the Fascist tide there. He aimed to take refuge in America, but his first stop on the way to New York was Venice, a city he loved dearly. In this novel he calls it ‘a wonder of the world’.

Daily life in Budapest was still undisturbed in 1933. Molnár was seen daily in his straw hat, sparkling monocle in the right eye, strolling along the Duna Corso, the promenade on the Pest side of the Danube, stretching from the Elisabeth Bridge to the Chain Bridge. Already a well-known dramatist and writer in Europe and America, he was greeted at every step, even by friendly strangers. The Athenaeum publishing house asked him for a new novel. What should he write about? He submitted a manuscript without much of a story, its title inspired by a little flute-blowing putto at the bottom of Bellini’s Madonna in the Frari church in Venice. In essence, the story is a love triangle, a romance coloured with intrigue and jealousy. Molnár, with the skill of a psychologist, describes a young woman on the verge of becoming a grown-up, still unversed in the complications of adult life, still a dreamer. The action is played out against the backdrop of the Venice which Molnár knew so well, with its fascinating history and its narrow little alleyways.

He maintains that living abroad makes one different. Does it? Perhaps less so today than it did in Molnár’s time. Now the world’s populace is becoming a global melting pot of nationalities and races. But the main theme remains eternal. The protagonists come into sharp focus in Molnár’s mirror. A mirror which is able to show not only virtues, but every human foible and frailty.

Mátyás Sárközi

Hampstead, 2024

Wrong Passport – a John Sandoe recommendation

Good to see Wrong Passport, Ralph Brewster’s extraordinary memoir of life on the run in wartime Budapest and flight westwards ahead of the advancing Russian troops, included as one of top London bookshop John Sandoe‘s recommended reads»

“New edition of a remarkable memoir by an Italian-born American, first published in 1954, which describes how it was to live in Nazi-occupied Budapest in 1943-45.”

Mrs Anderson as Sherlock Holmes, love interest Tibor as Watson

Good to see Bas Bleu featuring Blue Danube’s Mrs Anderson as one of their summer “mystery” titles.

Here » for their excellent summary (and attractively discounted price!).

“Accompanying Milla [the Mrs Anderson of the title] is the romantic but comically clueless Tibor Vida, a struggling Hungarian composer who serves as both her love interest and the Dr. Watson to her Sherlock Holmes.” Read more »

With some great reviews too:

Works by Leonardo in Budapest

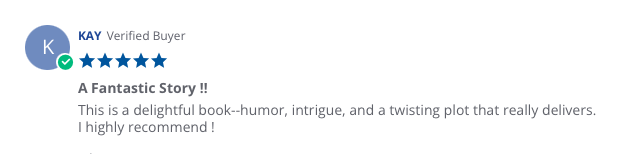

Miklós Bánffy’s story of The Remarkable Mrs Anderson is centred on a fictitious work of art, a Head of Christ by Leonardo da Vinci, stolen from the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. No such work exists but the basic premise is not implausible. The Museum of Fine Arts is one of the finest galleries of its kind in the world and it does possess some works by Leonardo da Vinci.

To be exact, it possesses four. Three of them are drawings (not on permanent display because of their fragility) and the fourth is a small bronze.

The earliest work is a study of horses’ legs, executed in black chalk and thought to date from the early 1480s, when Leonardo was in Milan. The artist had gone there in 1482 or 1483 to offer his services to Ludovico Sforza, known as ‘Il Moro’. Ludovico commissioned a gigantic equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza, soldier of fortune and founder of the Sforza dynasty, who had ruled Milan from 1450–66. No finished monument ever materialised. A clay model was produced but it was destroyed by French troops when they claimed Milan and took Il Moro into captivity. In Vigevano, the town southwest of Milan where Il Moro was born, in the vast Castello Visconteo Sforzesco, the Leonardiana museum has a detailed section devoted to the planning of this monument. The Budapest study drawing of horses’ legs is thought to have been prepared during the planning of that monument, perhaps drawn from life from one of the steeds in the great Sforza stables which are still to be seen in the castle at Vigevano.

Budapest’s two other Leonardo drawings are studies of warriors’ heads, one in charcoal and the other in red chalk and both probably made when Leonardo was back in his native Florence, where the city governors had commissioned a mural for Palazzo Vecchio. Once again it was a commission whose subject matter harked back to past valour, this time victory over Milan at the battle of Anghiari, which was fought in 1440. And once again the work was never completed: Leonardo had been trying to formulate a new mural-painting technique, an experiment which ended in failure. What we know of the composition of the work comes from a drawing by Rubens, now in the Louvre, of its central section, possibly derived from Leonardo’s own cartoon. The two Budapest drawings, by Leonardo’s hand, are studies for the heads of some of the combatants, hoary and partially toothless old condottieri remorselessly slugging it out.

The fourth Budapest Leonardo is a small bronze of a rearing horse and its rider, naked but for his elaborate helmet. The whole ensemble stands just over 24cm high. It was bought by the Hungarian Neoclassical sculptor István Ferenczy while he was in Rome studying under Bertel Thorvaldsen. This would have been sometime between 1818 and 1824. Anything else about the provenance of the sculpture is unknown. In fact, the true identity of its sculptor is unknown. When it was first acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, just before WWI, it was displayed as a Leonardo. Today scholars are more cautious. There were even suggestions that it was a 19th-century copy but those fears were laid to rest in 2009, following painstaking studies in Washington. The attribution to Leonardo remains, but the little bronze may in fact be the work of one of the master’s wide circle of imitators. The debate goes on and the little horse and rider now have their very own website devoted to their story.

Love-letters from Marie-Antoinette and Bánffy’s Danse Macabre

Je vais finir, non pas sans vous dire mon cher et bien tendre ami que je vous aime à la folie et que jamais jamais je ne puis être un moment sans vous adorer.

[I will not finish without telling you my dear and tender friend that I love you to madness and I can never never exist for a moment without adoring you.]

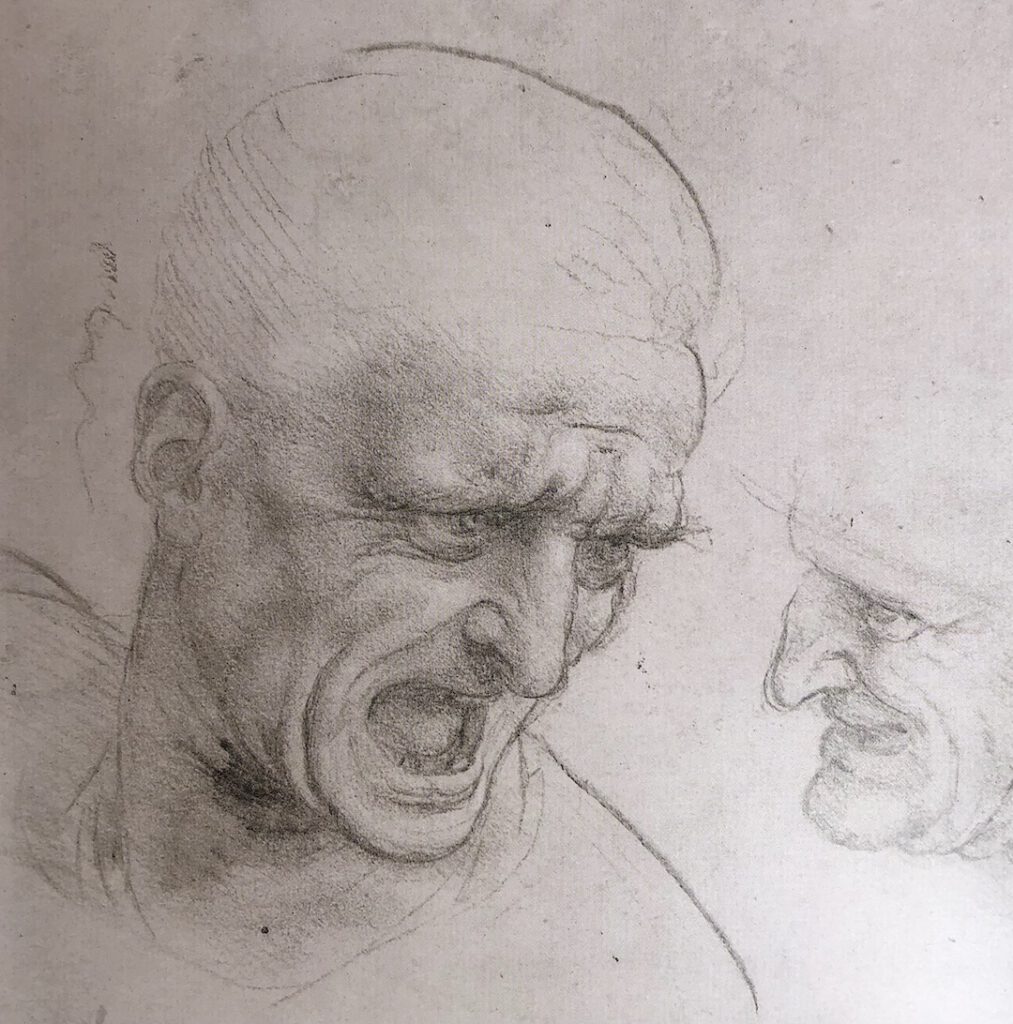

Thus Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France, concluded a letter to the Swedish nobleman Axel Fersen, on the 4th of January 1792. Rumours of an affair between the two were rife even in their lifetimes. Miklós Bánffy clearly believed them: the forbidden love between the queen and Fersen forms the subject of his poignantly painful short story Danse Macabre (included in Somerset Books’ collection The Monkey and other stories – details»). It is only now, thanks to research conducted by scientists at the Sorbonne and published earlier this month in Science Advances, the open-access journal of the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science), that the full texts of Marie-Antoinette’s letters to Fersen have been revealed.

In late June 1791, after a failed attempt to flee Paris (an escape bid which Fersen had partly orchestrated), the French royal family were placed under house arrest in the Tuileries. There they remained until the late summer of 1792 and it is from there that Marie-Antoinette wrote to her tendre ami. Those letters remained in Fersen’s family until forty years ago, when they were sold to the French National Archives. Because their content is sensitive—politically as well as personally—someone went through the letters and expunged any potentially compromising sections by carefully covering them with swirls of thick black ink, rendering them completely illegible. Until now, that is.

Using a technique known as X-ray fluorescent spectroscopy, the doodled-on parts of the letters have been carefully studied. The XRF scans can detect different inks and map them according to their chemical composition, specifically for potassium, magnesium, iron, copper and zinc. Looked at with the naked eye, for example, the sentence quoted at the beginning of this piece is completely invisible, hidden by a black scrawl, but it shows up clearly in the scan when the copper map is used. Studies of the ink used to scribble over the sensitive sentences seem to show that it was Fersen himself who was the censor.

Axel Fersen, soldier, diplomat and politician, spent much of his career in France. He was the same age as Marie-Antoinette: they were both born in 1755. A sympathy grew up between them and Fersen became a member of the queen’s intimate Petit Trianon set. This perceived favouritism became the cause of widespread resentment and cruel, sniping rumour, all memorably portrayed by Bánffy in Danse Macabre. According to Fersten’s friend Barrington Beaumont, it was to calm things down at court that Fersen went to America to fight alongside George Washington, since in France it was all the rage to celebrate American republicanism. Fersen’s departure forms the climax of Bánffy’s story, just as French court ladies are fawning over Benjamin Franklin, ‘enthralled at the idea of liberty for the people. Liberté, the word was presently in vogue at court…’ It is tempting to wonder whether Bánffy had read Beaumont’s memoirs. He may also have read Fersen’s letters. A passage dating from the winter of 1788 in which Fersen speaks of all men’s minds being ‘a ferment. Nothing is talked of but a constitution…It is a mania, everybody…can talk only of progress; the lackeys in the antechambers are occupied in reading the pamphlets that come out, ten or twelve in a day…’ could have been the model for the scene in Danse Macabre where Fersen leaves the palace: ‘In the middle of the wide atrium stood a group of liveried footmen. They were reading passages from a pamphlet which one man held half hidden beneath his coat, and at almost every line they let out loud guffaws, half amused and half appalled by the author’s effrontery. “She’s the crowned whore,” the man who held the book read aloud. “And the best thing to do would be to strangle her in her bed.” ’

The Monkey and other stories by Miklós Bánffy, translated by Thomas Sneddon and including Danse Macabre is published by Somerset Books – details»)

Marie-Antoinette’s fate is well known. Axel Fersen’s death was hardly less brutal. He was torn to death by a mob in Stockholm in 1810, at at time of violent disputes over succession to the Swedish throne. He never married. Perhaps, to borrow Bánffy’s words, Marie-Antoinette had been the only woman for whom his heart had ever learned to beat.

To read more detail about the Sorbonne scientist’s discoveries and scanning technique, and about the implications of their technology not just for revealing the past’s tender secrets, see here.

Bánffy translations reviewed

In The Bookseller:

Blue Guides launches literary imprint »

On HLO:

Blue Guides Release Two Books by Miklós Bánffy »

In The Lady:

In The Oldie:

2. Budapest 1900, by John Lukacs. Written in strikingly beautiful prose, Budapest 1900 guides the reader through a city which, though utterly different in many regards, still remains strikingly familiar architecturally. Budapest at the turn of the 20th century was a vibrant, dynamic, young city; it produced, in this era, such figures as Bartók, Kodály and von Neumann, and Bánffy spent much time in the city as a young parliamentarian. Incidentally, it also provides a lucid and concise summary of the political events which perplex so many readers of Bánffy’s Trilogy.

2. Budapest 1900, by John Lukacs. Written in strikingly beautiful prose, Budapest 1900 guides the reader through a city which, though utterly different in many regards, still remains strikingly familiar architecturally. Budapest at the turn of the 20th century was a vibrant, dynamic, young city; it produced, in this era, such figures as Bartók, Kodály and von Neumann, and Bánffy spent much time in the city as a young parliamentarian. Incidentally, it also provides a lucid and concise summary of the political events which perplex so many readers of Bánffy’s Trilogy.  4. The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary, by Bryan Cartledge. There are a number of good histories of Hungary, but most (for perfectly good reasons) focus on events in the 19th and 20th centuries. Cartledge provides the fullest account I know in English of certain historical periods, such as Transylvania’s 17th-century independence, that helped form Bánffy’s identity as both a Hungarian and a Transylvanian. It is, moreover, a tremendous work of scholarship.

4. The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary, by Bryan Cartledge. There are a number of good histories of Hungary, but most (for perfectly good reasons) focus on events in the 19th and 20th centuries. Cartledge provides the fullest account I know in English of certain historical periods, such as Transylvania’s 17th-century independence, that helped form Bánffy’s identity as both a Hungarian and a Transylvanian. It is, moreover, a tremendous work of scholarship.  6. Between the Woods and the Water, by Patrick Leigh Fermor. The second book in Leigh Fermor’s account of a youthful trek across Europe in the mid-1930s leads him into Transylvania, and to lengthy encounters with much the sort of characters whom Bánffy describes in his fiction. Much has changed since the pre-war days, of course, and the people he meets live in greatly reduced circumstances (Bánffy tells a remarkably similar story of an encounter between a young Englishman and Transylvanian gentry trying to conceal their poverty in his short story Somewhere) but though diminished, it is still recognisably the same world, while Leigh Fermor’s writing is, as fans will know, superb throughout.

6. Between the Woods and the Water, by Patrick Leigh Fermor. The second book in Leigh Fermor’s account of a youthful trek across Europe in the mid-1930s leads him into Transylvania, and to lengthy encounters with much the sort of characters whom Bánffy describes in his fiction. Much has changed since the pre-war days, of course, and the people he meets live in greatly reduced circumstances (Bánffy tells a remarkably similar story of an encounter between a young Englishman and Transylvanian gentry trying to conceal their poverty in his short story Somewhere) but though diminished, it is still recognisably the same world, while Leigh Fermor’s writing is, as fans will know, superb throughout.