Je vais finir, non pas sans vous dire mon cher et bien tendre ami que je vous aime à la folie et que jamais jamais je ne puis être un moment sans vous adorer.

[I will not finish without telling you my dear and tender friend that I love you to madness and I can never never exist for a moment without adoring you.]

Thus Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France, concluded a letter to the Swedish nobleman Axel Fersen, on the 4th of January 1792. Rumours of an affair between the two were rife even in their lifetimes. Miklós Bánffy clearly believed them: the forbidden love between the queen and Fersen forms the subject of his poignantly painful short story Danse Macabre (included in Somerset Books’ collection The Monkey and other stories – details»). It is only now, thanks to research conducted by scientists at the Sorbonne and published earlier this month in Science Advances, the open-access journal of the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science), that the full texts of Marie-Antoinette’s letters to Fersen have been revealed.

In late June 1791, after a failed attempt to flee Paris (an escape bid which Fersen had partly orchestrated), the French royal family were placed under house arrest in the Tuileries. There they remained until the late summer of 1792 and it is from there that Marie-Antoinette wrote to her tendre ami. Those letters remained in Fersen’s family until forty years ago, when they were sold to the French National Archives. Because their content is sensitive—politically as well as personally—someone went through the letters and expunged any potentially compromising sections by carefully covering them with swirls of thick black ink, rendering them completely illegible. Until now, that is.

Using a technique known as X-ray fluorescent spectroscopy, the doodled-on parts of the letters have been carefully studied. The XRF scans can detect different inks and map them according to their chemical composition, specifically for potassium, magnesium, iron, copper and zinc. Looked at with the naked eye, for example, the sentence quoted at the beginning of this piece is completely invisible, hidden by a black scrawl, but it shows up clearly in the scan when the copper map is used. Studies of the ink used to scribble over the sensitive sentences seem to show that it was Fersen himself who was the censor.

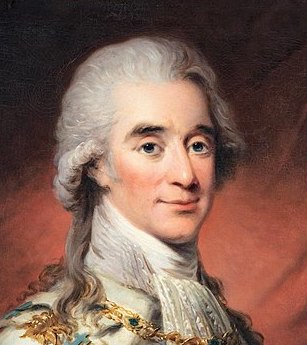

Axel Fersen, soldier, diplomat and politician, spent much of his career in France. He was the same age as Marie-Antoinette: they were both born in 1755. A sympathy grew up between them and Fersen became a member of the queen’s intimate Petit Trianon set. This perceived favouritism became the cause of widespread resentment and cruel, sniping rumour, all memorably portrayed by Bánffy in Danse Macabre. According to Fersten’s friend Barrington Beaumont, it was to calm things down at court that Fersen went to America to fight alongside George Washington, since in France it was all the rage to celebrate American republicanism. Fersen’s departure forms the climax of Bánffy’s story, just as French court ladies are fawning over Benjamin Franklin, ‘enthralled at the idea of liberty for the people. Liberté, the word was presently in vogue at court…’ It is tempting to wonder whether Bánffy had read Beaumont’s memoirs. He may also have read Fersen’s letters. A passage dating from the winter of 1788 in which Fersen speaks of all men’s minds being ‘a ferment. Nothing is talked of but a constitution…It is a mania, everybody…can talk only of progress; the lackeys in the antechambers are occupied in reading the pamphlets that come out, ten or twelve in a day…’ could have been the model for the scene in Danse Macabre where Fersen leaves the palace: ‘In the middle of the wide atrium stood a group of liveried footmen. They were reading passages from a pamphlet which one man held half hidden beneath his coat, and at almost every line they let out loud guffaws, half amused and half appalled by the author’s effrontery. “She’s the crowned whore,” the man who held the book read aloud. “And the best thing to do would be to strangle her in her bed.” ’

The Monkey and other stories by Miklós Bánffy, translated by Thomas Sneddon and including Danse Macabre is published by Somerset Books – details»)

Marie-Antoinette’s fate is well known. Axel Fersen’s death was hardly less brutal. He was torn to death by a mob in Stockholm in 1810, at at time of violent disputes over succession to the Swedish throne. He never married. Perhaps, to borrow Bánffy’s words, Marie-Antoinette had been the only woman for whom his heart had ever learned to beat.

To read more detail about the Sorbonne scientist’s discoveries and scanning technique, and about the implications of their technology not just for revealing the past’s tender secrets, see here.