‘Calamity! On the 14th of December a painting by Leonardo da Vinci—and not some careless, half-finished sketch, but a genuine masterpiece—was stolen from the Budapest Fine Arts Museum.’ So begins Miklós Bánffy’s funny, fast-paced, nostalgic novella The Remarkable Mrs Anderson.

But what painting did Bánffy have in mind? The Budapest Fine Arts Museum does possess some works by Leonardo. There is a small bronze statuette of a horse and rider, which is attributed to him, and some sketches that are certainly by his hand (studies of soldiers’ heads and horses’ legs). There is no Head of Christ, though. For that, we have to go to Milan, to the Pinacoteca di Brera, where there is a charcoal drawing that might have inspired Bánffy.

The painting stolen in The Remarkable Mrs Anderson measured 44.7 by 35.1 centimetres. The one pictured above measures 40 by 32. Was this what Bánffy had in mind? Perhaps. But the Brera only attributes it to a ‘Lombard artist’, not definitely to Leonardo. And it is a drawing on paper. Bánffy makes it clear that the picture in his story is a finished painting, in full colour, on a wooden board.

So was it something like the Salvator Mundi, perhaps, now owned by Louvre Abu Dhabi?

The Salvator Mundi is painted in oil on a walnut panel, but it is far too tall (65cm). And its full-frontal pose is nothing like the work that Bánffy had in mind, which depicts ‘the same figure who later represents Jesus in the Last Supper‘. Bánffy was thinking of something much more along the lines of the Brera image. ‘Experts surmise that the master was perfecting his technique, working from the original model and preparing for the great fresco to come.’

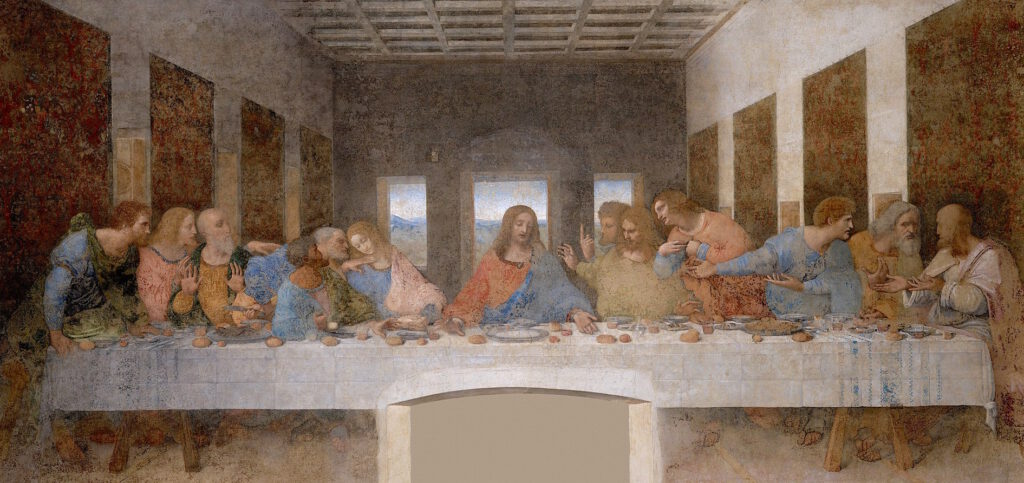

Leonardo painted his Last Supper on the refectory wall of the Dominican friary of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. Christ’s side-on pose, with eyes cast down, is clear to see:

The Last Supper is also, as Bánffy knew, in poor condition: ‘badly faded,’ as he puts it. Alta Macadam, in Blue Guide Lombardy (1st ed. 2019) tells us that ‘The Last Supper is painted with a technique peculiar to Leonardo, in tempera with the addition of later oil varnishes, on a prepared surface in two layers on the plastered wall. It is therefore not a fresco. In fresco-painting, pigments are dissolved in water and then painted onto a surface primed with fresh lime plaster. If the climate is dry, true frescoes will retain their brightness for an exceptionally long time. In Leonardo’s work, errors in the preparation of the plaster, together with the dampness of the wall, have caused great damage to the painted surface, which had already considerably deteriorated by the beginning of the 16th century. The Last Supper has been restored repeatedly and was twice repainted (in oils) in the 18th century. Careful work (begun in 1978 and completed in 1999) was carried out to eliminate the false restorations of the past and to expose the original work of Leonardo as far as possible.’

Bánffy was an accomplished amateur painter himself; he would have understood about plaster and water, about oil and pigments and varnishes. It is his own beguiling fantasy, that the Fine Arts Museum in Budapest possessed a small Head of Christ, a study work in which Leonardo experimented with his own peculiar technique, not on plaster but on wood, and which yielded a result that did not fade.

Annabel Barber